15 February 2025

From the ground up: ten years of SIS

Ten years ago, the Irish Soils Information System (SIS) was launched. Senior Research Officer Réamonn Fealy reviews its historical context, development and usage – and considers emerging demands for soil data and how these may be met by technology.

Due to the legacy of the Ice Ages in Ireland, soil mapping is particularly difficult here. While in some parts of the country the evidence is obvious, as in the classic drumlin landscapes, in other areas the signs are not so apparent. However, 1,000-metre-high sheets of ice traversing and ploughing up our landscape over millennia have had a profound impact on the development of soils that followed the retreat of that ice. Due to this tumultuous geological history, the pattern of Irish soils is complex and mapping them is a challenging task, explains Réamonn Fealy, a Senior Research Officer at Teagasc Ashtown specialising in geo-spatial analysis.

“In contrast to many other areas of the world, there is considerable spatial variation evident, with subsoils and topography varying over short distances, giving rise to multiple soil types often occurring close together. Of the 11 major soil types found in Ireland, nine of them were once mapped in a single field in Cork!”

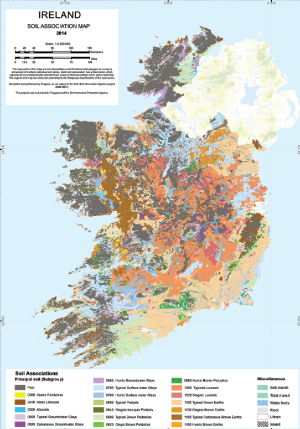

Image credit: Irish Soil Information System

Charting the unknown

In 1959, the National Soil Survey (NSS) was established within An Foras Talúntais (AFS). Its aim was to survey the soils in Ireland with a focus on agricultural potential, particularly grazing potential, and later to assess the distribution of marginal lands for the EEC Disadvantaged Areas Schemes.

“When the NSS finished in the early 1980s, approximately 44% of the country had been published by county at 1:126,720 scale – or ½ inch:1 mile,” Réamonn continues. “The second edition of the General Soils Map had been published at a scale of 1:575,000 and was based on a combination of both surveyed information and the application of derived soil landscape knowledge to areas not previously surveyed.”

In 1998, in response to European legislation, and arising from the fact that over 56% of the country remained unmapped, Teagasc was tasked with producing the national Irish Forest Soils (IFS) Map. The map combined novel remote sensing and Geographical Information Systems (GIS) techniques, along with data from the previous soil survey, to create a predictive model of indicative soil types for previously unmapped areas. The national response to a subsequent initiative to produce a harmonised soils map for Europe led to the early conceptualisation of the Irish Soils Information System (SIS), explains Réamonn.

“With the original design scoped out in 2007 by Teagasc research officer Karen Daly and myself, an EPA and Teagasc co-funded collaboration ultimately led to the creation of a comprehensive database of the soil types in Ireland. With this came the development of a new national map of soil associations at a scale of 1:250,000.”

The SIS project built on the existing county surveys and IFS mapping, and in an extensive sampling effort provided additional field data collection for the counties not previously covered by the National Soil Survey. Cutting-edge models were developed for predictive mapping using landscape type and a wide range of environmental variables. The public website provides freely available access to the map and a database of soil types with detailed descriptions of the soil types occurring in Ireland.

A machine for collecting soil spectra in the lab at Johnstown Castle. Photo credit: Andrew Downes

Targeting solutions

“Building on the work of our predecessors in AFS, the SIS 1:250,000 map was a remarkable achievement over a relatively short space of time and points towards exciting possibilities for the future,” Réamonn continues. “Since its launch, it has attracted significant attention both nationally and internationally. Over 100,000 users have visited the SIS website with more than 80,000 of those users recorded from Ireland.”

Despite significant advancements, there remains plenty of work to be done, he adds.

“The smallest area that can be represented on a map at 1:250,000 scale with any degree of confidence is approximately 250 hectares. To give you an idea, that’s the equivalent size of roughly 38 Croke Parks or about eight farms of average size in Ireland. Emerging trends point to the need for new, more highly resolved data on Irish soils.”

Foremost among these trends is the increasing focus on environmental sustainability, which requires farmers to implement measures to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, enhance carbon sequestration, improve water quality and restore biodiversity, explains Karl Richards, Head of Teagasc’s Climate Centre.

“Targeted solutions are needed to ensure that the right measure is located in the right place at the right time to maximise impact. This requires higher spatial and temporal resolution of soil data. The Teagasc Climate Centre focuses on developing technical solutions to achieve the climate and biodiversity goals for agriculture and increasing the resolution of soil data will be key to this.”

Increasingly, consumers and food purchasers are demanding access to verifiable sustainability data relating to the food they buy and eat. Farmers want to be able to measure the impact and improvements they make on their farms, continues Karl.

“Carbon farming, the soil health law, nature restoration law, all will require improved soil data at a higher spatial and temporal resolution. In the future, tools like Nutrient Management Planning (NMP) Online and the sustainability support framework AgNAV will likely need to include farm- and field-specific soil data to verifiably measure and report on areas such as carbon sequestration and soil biodiversity.”

To help improve soil surveying and mapping, new research is looking at ways to make soil data collection easier, cheaper and faster, explains Karen Daly, Principal Research Officer at Teagasc Johnstown Castle.

“For the analysis of soil properties, Teagasc is developing and applying a well-known technique called infrared spectroscopy – used frequently in pharmaceutical sample analysis. When an IR light is shone on soil samples, an image or spectrograph is produced, which is like a fingerprint of that soil sample. The application of machine learning techniques enables us to turn those images into information and use data science to make sense of it. With a single scan, we can now measure up to 15 soil parameters without any chemicals for preparation.”

Réamonn concludes: “In view of both emerging and future user requirements leading to soil data becoming increasingly prioritised, it is inevitable that the Irish soil data project will need to both continue and to be reinforced. It seems the historical words of R. S. Smith, Director in the United States Soil Survey, have never been truer!”

“…the soil survey will never be completed because I cannot conceive of a time when knowledge of soils will be complete. Our expectation is that our successors will build on what has been done, as we are building on the work of our predecessors.”

R. S. Smith, Director Illinois Soil Survey, 1928

Soil Spectropy Technologist Felipe Bachion de Santana preps instruments for analysis. Andrew Downes, xposure

Funding

This project was co-funded by Teagasc and the Environmental Protection Agency (STRIVE Research Programme 2007-2013).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the huge input to the development of SIS by all of the project team at Teagasc, Cranfield University and University College Dublin, and the collective input of over 30 project staff members that contributed at various times over the duration of the project.

Contributors

- Réamonn Fealy, Senior Research Officer, Rural Economy and Development Programme, Teagasc Ashtown. reamonn.fealy@teagasc.ie

- Karen Daly, Principal Research Officer, Crops, Environment and Land-Use Programme, Teagasc Johnstown Castle.

- Lilian O’Sullivan, Senior Research Officer, Crops, Environment and Land-Use Programme, Teagasc Johnstown Castle.

- Karl Richards, Head of Teagasc, Climate Centre, Teagasc Johnstown Castle.

This article was first published in TResearch Winter 2024