07 May 2023

How will changes to Pillar I payments affect farmers?

Pillar I Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) support represents a significant proportion of income for certain cohorts of the farming population. Researchers at Teagasc set out to examine what the changes to how the support is distributed mean.

Research undertaken by economists in Teagasc suggests that the changes to the Pillar I Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) will not significantly impact the number of farms that are economically viable.

Fiona Thorne, one of the authors of the report, says: “The change in incomes that result from the Pillar I CAP reform are, in general, small relative to the scale of the income changes required to shift farms from being economically unviable to economically viable.”

As part of the CAP reform process, the new CAP strategic plan for Ireland came into operation from 1 January 2023. New research by Teagasc examines the impact of the reforms to the implementation of Pillar I under the new agreed CAP strategic plan for Ireland, 2023-2027. The analysis did not consider the changes to Pillar II under the recently approved CAP Strategic Plan.

Key changes of new Strategic Plan

Pillar I CAP support in Ireland’s National Strategic Plan includes:

- Capping: further continuation of capping of payments.

- BISS: a ring-fenced percentage of the direct payments ceiling to be paid as a Basic Income Support for Sustainability (BISS).

- Eco Schemes: an allocation of 25% of the direct payments ceiling to eco-schemes reflects the strong environmental ambition of the CAP programme.

- CRISS: redistribution of funds by front-loading direct payments through the Complementary Redistributive Income Support for Sustainability (CRISS) scheme.

- Internal convergence: continuing convergence of payment entitlement values – a process to redistribute and flatten the value of payment entitlements in Ireland.

- National Reserve: a minimum ring-fenced sum for generational renewal (3%).

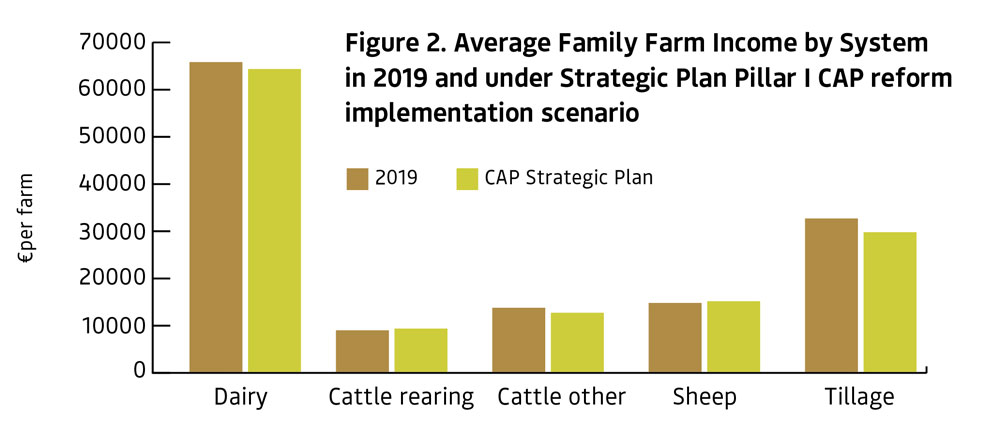

In general, specialist dairy farms tend to have a lower reliance on Pillar I direct payment support as a source of Family Farm Income (FFI) compared with other farm systems, while specialist cattle systems – such as cattle rearing and cattle other – tend to be the most reliant on direct income support.

“Based on data from 2019,” says Fiona, “other things being equal, a 10% reduction in the combined Basic Payment Support scheme and Greening payments [schemes from the Pillar I support from CAP 2015-2019] received by specialist dairy farms would reduce FFI on these farms by 7%. However, a 10% reduction in these supports provided to cattle farms would lead to an FFI reduction of approximately 25%.”

Conducting the research

Teagasc National Farm Survey (NFS) data from 2019 was the main source of information used in this analysis. The NFS surveyed a sample of 878 farms representing a farm population of 92,190 farms. ‘Small’ farms – those with a standard farm output of less than €8,000 – are excluded from the annual NFS sampling frame.

The Teagasc analysis was based on the CAP Strategic Plan 2023-2027 submitted by Ireland and agreed by the European Commission in 2022. The analysis assumes an average BISS of €156.18 per ha, with all farmers receiving at least 85% of this level by 2027; an eco-scheme payment of €77 per ha; and a CRISS payment of €43 on the first 30 hectares of each holding. The mandatory inclusion of a convergence strategy for Pillar I payments in this CAP reform implies reduced levels of income support for some cohorts of the population, while providing additional levels of income support to other cohorts.

Distributional impact of the reform

The results (Figure 2) show that the simulated effect on FFI at a farm level as a result of the Pillar I CAP reform depends on an individual farm’s starting position in terms of its Basic Payment Scheme level and Greening payment per hectare (both components of the CAP scheme 2015-2019), and the importance of Pillar I direct income subsidies in the farm’s overall FFI.

For the average farmer, the change in income that would be experienced as a result of the CAP reform of Pillar I payments is relatively small. Figure shows that, on average, dairy, tillage and cattle other farms will be worse off than they were before the reform was implemented, with sheep and cattle rearing farms gaining on average as a result of the implementation of the reform.

Only a small proportion of specialist tillage farms gain in terms of direct income support receipts or FFI under the CAP reform analysed. However, in contrast to the implications of the scenario for dairy farm incomes, a considerable proportion of specialist tillage farms would experience a rededication in income effects of at least 10% under the CAP reform scenario.

Unlike dairy and tillage farms, the implications for specialist sheep farms are more mixed when the proportion of sheep farms represented by those in income gain and loss categories is examined. Just over half of specialist sheep farms represented by the Teagasc NFS would gain in terms of a change in FFI when the reform, as analysed in the Teagasc report, is fully implemented.

The pattern of income gains and losses is different for the two specialist cattle systems. The proportion of farms losing in terms of changes in FFI under the reform is greater for cattle other (mainly finishers) farms than it is for cattle rearing farms, where a slightly greater proportion of the farms represented by the NFS see gains in income due to the CAP reform.

A greater number of ‘small’ farms gain in income rather than lose under the CAP reform relative to income in the status quo.

Fiona concludes: “Focusing on the proportion of output produced by gaining and losing farms, the value of output produced by farms gaining under the reform was less than the value of output produced by the farms experiencing losses in income as a result of the CAP reform.

“The implication is that farmers who benefit from the changes to Pillar I payments tend to produce less agricultural output.”

Figure 1. A summary of the decomposition of the Pillar I CAP budget for Ireland.

Figure 2. Average Family Farm Income by System in 2019 and under Strategic Plan Pillar I CAP reform implementation scenario

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the staff of the Teagasc National Farm Survey involved in the collection and validation of the data, and the farmers who voluntarily participated in the National Farm Survey. The authors are also grateful to the staff of Department of Agriculture, Food and the Marine for the provision of administrative data used in defining the policy assumptions necessary for the analysis.

Contributors

Fiona Thorne, Senior Research Officer, Agricultural Economics and Farm Surveys Department, Teagasc

Trevor Donnellan, Head of Department, Agricultural Economics and Farm Surveys, Teagasc

Kevin Hanrahan, Head of Programme, Rural Economy and Development Programme, Teagasc

This article first appeared in the Spring edition of TResearch.