05 July 2023

Dosing advice to slow the build-up of resistance

There is a huge issue around the use of not only antibiotics but also anthelmintics on farms in Ireland and around the world. Martina Harrington, Teagasc Beef Specialist, explains that the main concern is the rate at which resistance to these products is building.

Worms can only become resistant if they are exposed to the doses. Therefore, we as farmers need a more holistic approach towards the treatment of worms and diseases on our farms to slow the build-up of resistance. The alternative is frightening. What if no wormer works on your farm? What if very few antibiotics work on your farm? What will be the solution then?

The results from a study carried out by Dr. Orla Keane in Teagasc showed the levels of resistance on 24 Irish dairy calf to beef farms (table below).

| Anthelmintic class | No. of farms tested | No. of farms with resistance | Prevalence of resistance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Benzimidazole (1-BZ) | 17 | 12 | 71% |

| Levamisole (2-LV) | 12 | 3 | 25% |

| Macrocyclic lactone (3-ML; Ivermectin) | 17 | 17 | 100% |

| Macrocyclic lactone (3-ML; Moxidectin) | 12 | 9 | 75% |

100% of the farms showed resistance to ivermectins, why? Ivermectins are easy to use, you can inject or pour-on, so could say they have been overused. The levamisole resistance is low at 25%, why? It is a messy, high volume dose and farmers have been less likely to use such doses. This proves that less exposure equals less resistance.

Slowing the build-up of resistance

One of the ways to slow the build-up of resistance is to reduce the exposure of worms to these products – only dose when you have to. So how do you know when you have to dose?

One way of knowing is to use faecal egg samples. This is where you take a fresh sample of dung from at least 10 animals and send it to the lab to test for the presence of eggs. Once the level of the eggs exceeds a threshold of 250 eggs per gram in cattle, then you go in with a dose using best practice (outlined below).

Labour saving

From working with the Future Beef farmers, we have seen that the point when animals become infected can vary wildly. For suckler calves, they have to consume a significant level of grass to pick up larvae. Dairy calves on the other hand are eating grass from their first week out.

If you assume calves have worms and you dose today, you have wasted a dose and more importantly a significant amount of time getting them in etc. If the infection occurs two weeks later, then you may not be dosing for weeks and miss the infection; you then lose performance and have to dose again. By faecal sampling every 2-3 weeks when animals are at grass, you can pick exactly when to dose and build up a picture of infection on your farm.

However, a word of caution is needed. The above is the case for gut worms. In the case of lungworm or hoose, you go in and dose once you hear animals coughing. The reason for this is most damage is done by the larvae stage, i.e. before they become adults and start to lay eggs that appear in the dung.

Remember, fluke is usually not a problem at this time of year, so do not use combination products. If you have animals going to the factory, you should ask them to check their livers for fluke and react then.

Farmers’ experience of FEC sampling

A number of farmers in the Future Beef Programme are leading the way in this new approach and are using FEC tests on their farms to determine the requirement to dose or not. Not only have the farmers found it beneficial in determining the worm burden of their animals, it has also provided labour savings on farm.

Commenting on the use of FEC tests on his farm, John Dunne (pictured below), who farms in Portarlington, Co. Laois, explained: “Faecal egg sampling helps us decide whether to dose or not to dose. It is important to get the timing and anthelmintics type correct. Samples can save time and money while also helping prevent anthelmintics resistance.”

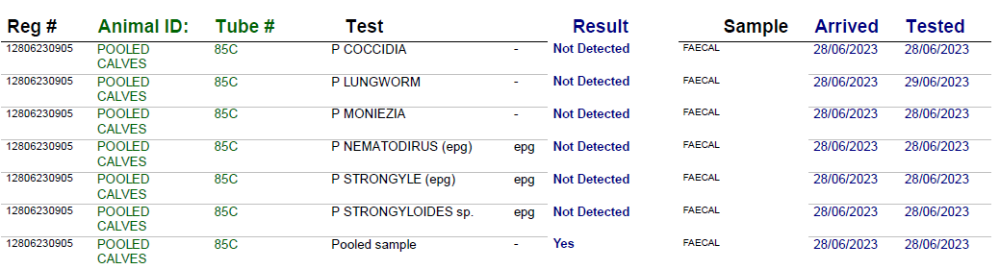

Figure 1 below highlights a recent test completed on John’s farm, which indicates that animals were not in need of a dose, as the presence of stomach worms was not detected.

Figure 1: FEC test results from John Dunne’s farm

James Skehan, another participant in the programme, this time based in Co. Clare, noted: “From a part-time farming point of view, it saves me from unnecessarily rounding up cattle and dosing them when they don’t need it.

James Skehan pictured with his family

“It’s a lot easier for me while herding my cattle to take a few samples, send them away and plan my dosing that way. Also you don’t need to be a genius or have 500 points in the leaving cert to understand the dangers of fluke/worms becoming resistant to dosing due to the ‘traditional, sure that’s how we always do it’ habit of dosing off the calendar.”

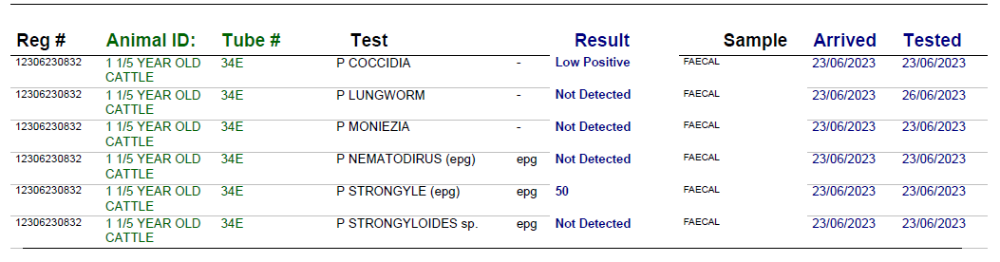

Another farmer who is utilising FEC testing on his farm is Co. Tipperary-based farmer John Barry, who said: “I tested last week wondering did the cattle have worms and it showed up with just a slight positive for coccidiosis. For stomach worms, it showed up at 50 eggs per gram (figure 2 below), so it was well worth doing the test. The cattle aren’t showing any clinical signs and there is no point in dosing if all the samples are clear, which would only waste time and money.”

John Barry pictured with Future Beef Programme Advisor Aisling Molloy

Figure 2: FEC test results from John Barry’s farm

Targeted Advisory Service on Animal Health (TASAH)

Currently there is a free service being provided by trained vets as part of the Targeted Advisory Service on Animal Health (TASAH). You simply logon to the Animal Health Ireland website, nominate your vet to carry out a herd or flock visit to look at various aspects of parasite control management on-farm. Then your vet will make recommendations and will conduct two faecal egg count tests for roundworms (stomach or gut worms). There is no cost to the herd or flock owner, as this is fully funded by the Department of Agriculture, Food and the Marine.

Natascha Meunier from Animal Health Ireland featured on a recent Beef Edge podcast to the Targeted Advisory Service on Animal Health (TASAH). Listen in below:

How to take a faecal egg sample

- Samples must be posted on the day of sampling.

- Take samples early in the week (ideally Monday or Tuesday) to avoid samples sitting the post over the weekend.

- Collect samples in the morning, after a period of rest.

- As calves are quietly disturbed, they should defecate in one spot.

- Worms are not evenly distributed. Faeces should be collected from three different areas of the same dung pat.

- 10 different samples from at least 10 different animals should be taken.

- Dung should be placed in sample pots and placed in sealed, air-tight, zip-lock bags.

- Don’t overfill the tube, two-thirds full is plenty.

- Fill in the required information on slip, the more information the better. Include recent dosing history.

- Post to the lab that day or a least within 24 hours of collection.

- Do not place samples in fridge.

- Do not freeze.

- Do not place in direct sunlight.

Best practice when dosing

- Ensure the correct dosing technique is used and that the animals are treated according to the manufacturer’s instructions and dose rates.

- Dosing equipment should be checked before treatment to ensure it is delivering the correct amount.

- Animals should be weighed or a few of the biggest animals in the group selected and weighed to determine the dose rate. All dosed to the weight of the heaviest animal.

- Continual use of anthelmintics from the same class should be avoided and combination anthelminthic products (flukicide + wormer) only used when it is necessary to target both fluke and worms.

- Keep the cleanest grazing such as reseeds, after grass, for the most naïve animals such as calves.

- Calves can also be grazed ahead of older animals or mixed with sheep to reduce the worm challenge.

- If using ivermectin in calves with say a 5 week persistency, calves should be dosed every 6-7 weeks to allow them to build natural immunity to worms

- Cows are immune to gut and stomach worms as should older cattle.

- A good biosecurity protocol for all bought-in animals should be implemented to prevent bringing resistant worms onto the farm. Bought in stock should be treated with an anthelmintic and housed for 48 hours. They should then be turned out to a contaminated pasture recently grazed by cattle.

Martina Harrington is the manager of the Future Beef Programme. For more inforation on this programme, click here.