30 July 2021

Seed Storage, Stratification and Germination of Some Popular Forestry Trees

“Though I do not believe that a plant will spring up where no seed has

been, I have great faith in a seed. Convince me that you have a seed

there, and I am prepared to expect wonders.”

― Henry David Thoreau 1817 – 1862.

Here, Oliver Sheridan, Teagasc Forestry Researcher discusses seed propagation

“Though I do not believe that a plant will spring up where no seed has

been, I have great faith in a seed. Convince me that you have a seed

there, and I am prepared to expect wonders.”

― Henry David Thoreau 1817 – 1862

The island of Ireland is fortunate in that the climate is, for the most part, a mild and moist oceanic climate due to its global location and the influence of the Gulf Stream. The climate is conducive to growing a wide range of trees both native and introduced species. Soil types throughout the Island of Ireland vary considerably so having the ability to grow such a wide range of trees offers the opportunity to match different tree species to specific soil types to achieve maximum growth and healthy trees.

While many plants multiply naturally by vegetative means, almost all trees produce seeds as their principle means of perpetuating the species. A seed is a fertilized ovule and represents the end product of gametasporagenesis (embryo sac development), pollination and fertilization. A mature fertilized ovule contains an embryo composed of a root radicle and shoot primordium. Seed formation and seed production for different tree species are complex while seed quality and quantity can be heavily influenced by environmental factors. However, man’s intervention, manipulation and knowledge of seed propagation take advantage of understanding these processes and in turn enables early assessments of potential seed crops to be carried out. Many nurserymen derive their livelihood from growing seedlings and without their intervention and knowledge of seed production and propagation processes would possibly lead to business failure over time. The modern nurseryman must have a good knowledge of seed orchards, provenance selection, seed production, storage facilities, dormancy treatments etc. to run a successful business. Afforestation, reforestation, genetic diversity and rootstock production are very much dependent on large scale nursery seedling production. Seed is also a more cost effective method of production compared to vegetative methods such as cuttings and grafting which generally require more sophisticated propagation facilities. There is less of a risk of virus transmission from one generation to the next from seed propagation compared to vegetative propagation.

Seed Storage

Seeds can be obtained from local sources (within Department Regulations for Forestry Reproductive Material (FRM)) or from commercial seedhouses. Seed storage is the period of time between collection/purchase of seed and sowing. The primary aim of storage is to retain seed at maximum viability for as long as possible. Viability refers to the proportion of seed that is live when a sample is assessed and therefore the potential number of seeds capable of germination. The term longevity refers to the length of time that seed may be successfully stored and still germinate satisfactorily. Freshly harvested seeds will have relatively high moisture content and will be actively respiring. It is important that appropriate handling is not delayed as it will lead to seeds deteriorating. Always remove fresh seeds from airtight containers as quickly as possible. The seeds can be placed in sacks or open boxes in a cool ventilated shed with little variation of temperature. This will allow seeds like birch and alder to remain in a satisfactory condition before cleaning.

Refrigerated cold storage is ideal for most species both prior to and after cleaning. However, many factors affect seed storage, for instance, moisture content for most seeds should be reduced down to 8 – 10% and placed in sealed containers to maintain this level. However, some species that produce nut type seed, for example, Aesculus, Juglans, Quercus, Castanea and Cedrus store all or part of their foods as fats, oils, waxes and some as proteins. If these seeds are allowed to dry below a critical level they will not imbibe in a way that will allow the food reserve to be used by the embryo and in turn will cause a decrease in viability. The moisture content for these type of nutty seeds should not be allowed to fall below 40%, while the moisture content for beech should not fall below 20 – 25%. Most species of this type do not lend themselves to long periods of storage (max one year) as loss of viability will occur.

Temperature is another very important factor when considering seed storage. In general, low temperatures coupled with low seed moisture content will increase longevity of seed viability. An ideal temperature range of 1 – 5oC will suit most tree species. Some seed species develop very hard seedcoats and can be stored for very long periods without any loss of viability, provided they are kept dry and stored in sealed containers in a fridge or cold store. Examples of these species include Robinia and Gleditsia, members of the Fabaceae (Leguminosae) family.

Seed Dormancy

If viable seeds do not germinate when placed in conditions suitable for germination, then the seeds are said to be dormant. Factors associated with seed dormancy include, (i) live seeds being incapable of imbibing, (ii) embryo development is curtailed, (iii) seeds incapable of biochemical reactions and (iv) immature embryo conditions. Some seeds only exhibit one of these factors but two may be involved, this latter case is referred to as double dormancy. Dormancy usually results from processes that occur during the seeds development, however, there are two other times when seed dormancy can develop (i) when excessive drying-out of the seed takes place during processing and storage, (ii) unfavourable conditions such as very high temperatures after sowing.

Types of seed dormancy and pre-sowing techniques to overcome dormancy

Physical dormancy – Hard seed coats

Hard seed coats make it difficult to take up water causing slow and irregular germination e.g. Robinia, Pinus, Eucalyptus etc.

Techniques used to overcome hard seed coats

Mechanical scarification – aim to reduce the thickness of the seed coat making it more permeable to water and air. This can be achieved by cracking, filing or chipping the seed coat.

Hot water soak

- 4 – 6 times the volume of water to seed

- 70 – 100oC for 18 -24 hours (may need to repeat)

- Imbibed seeds fall to the bottom

- Example, Robinia, Tilia

Acid scarification

- H2SO4 (Concentrated sulphuric acid)

- 2:1 acid /seed for 15 – 90 minutes depending on species

- Robinia 20 min. Gleditsia 90 min.

- Some ornamental species such as Gymnocladus dioica up to 3 hours and Rhus 5 – 6 hours.

Warm moist stratification

- Useful for seeds with hard seed coats as it encourages a more natural way of degrading the seed coat.

- Seeds mixed with moist peat and placed in a polythene bag at a temperature of 21 – 24oC for a specified time depending on the species.

Physical dormancy – Waxy Seed Coats

Some seeds have a waxy layer on the seed coat making it impermeable to water. The wax layer also protects the seed by preventing loss of water.

Treat the seeds to hot water soak

Physiological dormancy

This is a biochemical process in seeds and or seed coats that induce dormancy.

Causes of physiological dormancy

- Insufficient development of the embryo e.g. Fraxinus

- Biochemical factors caused by chemical inhibitors or the failure of chemical reactions that should make food reserves available to the developing embryo e.g. Sorbus, Betula

There are a number of plants in the Rosaceae family that chemical inhibitors are contained in the ripened flesh of the fruit and the chemical inhibitor is able to build up within the seed coat if the fleshy tissue remains on the seeds and not removed before storage. Some species experience double dormancy i.e. they possess two dormancy factors (one physical and one physiological) and must be given two treatments before germination will occur e.g. Tilia.

Techniques used to overcome Physiological Dormancy

Cold moist stratification

Five criteria that will determine the success of the treatment.

- Temperature level – depends on the provenance of the species. Warm temperature species may respond to 20oC while cold temperature species may only respond to temperatures below 5oC (temperature range of 1 – 5oC for temperate plants).

- Stratification medium Must retain moisture around the seed – use moist peat, sand, vermiculite, shredded leaf mould or mixtures of 1:1 or 4:1

- Time period 4 – 20 weeks

- Aeration maintained by turning the seed batches (prevents temperature and carbon dioxide build-up).

- Two ways to provide Cold Moist Stratification

- Mix with stratification medium

- Naked stratification – Soak seeds in water for 24 hours, drain off the water and surface dry the seeds, put in a plastic bag and refrigerate.

Warm Moist Stratification

- Moist medium

- Temperature 21 – 24o

- Time period 4 – 12 weeks

Purpose of warm moist stratification is twofold:-

- Aid the development of an underdeveloped embryo. In nature the seed obtains this warm period during the summer months following fertilization with the cold period being provided by the following winter. This means that the seed can germinate the next spring i.e. 18 months after fertilization. Warm moist stratification is an artificial means of providing the summer warmth.

- Soften and break down the seed coat.

Warm moist stratification is normally followed by a cold moist stratification period as many seeds requiring a warm temperature period also require a period of cold temperature i.e. they show double dormancy e.g. Fraxinus excelsior – collect seed when yellow in colour, mix with moist compost/peat and followed with a warm moist stratification at 210 C. for 8 weeks and then a cold moist stratification at 1 – 30 C. for 12 weeks.

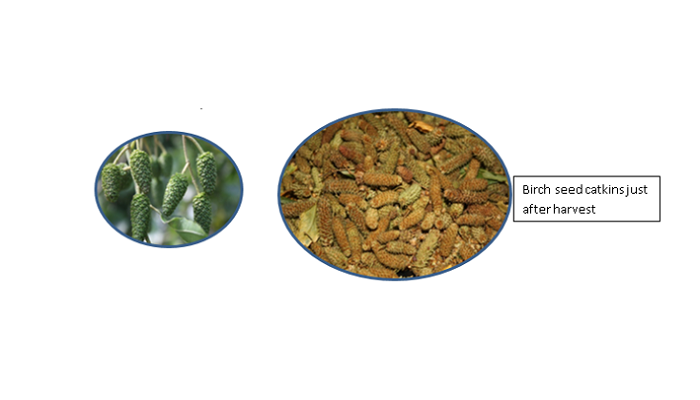

Alnus glutinosa (Common alder), Betula pubescens (Downy birch), Betula pendula (Silver birch)

Prior to spring sowing, soak the seeds in cold water for 24 hours, drain off the water, surface dry the seeds, place naked seeds in a plastic bag and refrigerate for four weeks at 1 – 4oC.

Castanea sativa (Sweet chestnut)

Nuts should be stored cool and kept moist in peat. Commercial samples from seedhouses that arrive dry should be soaked for 48 hours in cold water and if found to be viable store as above.

Nothofagus (Southern beech)

The fruits contain three nutlets and resemble those of Fagus sylvatica (common beech). The nutlets are of a fleshy nature and are prone to lose viability with excessive drying. Store the seeds at low temperatures (1 -3oC) ensuring to maintain the moisture content of the seeds. Mix seeds with damp peat and chill for six weeks before sowing.

Picea abies (Norway spruce), Picea glauca (White spruce), Picea sitchensis (Sitka spruce)

Harvest the cones before they ripen. A three week cold stratification should ensure a more uniform germination. The seeds will benefit from a 24 hour water pre-soak before spring sowing.

Prunus avium (Cherry)

It is desirable to clean the seeds of all pulp and juice as soon after collection as possible. Mix the seeds with a stratification medium (moist), give two weeks warm treatment (21 – 24oC) and 18 weeks cold stratification (1 – 4oC). Avoid high seedbed temperatures after sowing as this can induce secondary dormancy.

Pseudotsuga menziesii (Douglas fir)

Seeds are produced in cones and the cones should be collected just prior to the stage at which they open in autumn. The seeds can be extracted by drying the cones in a warm shed. Douglas fir seeds can be stored at low temperatures (c. 3oC) in a sealed container and as such will maintain viability for many years. Douglas fir exhibits embryo dormancy so a period of chilling is required prior to sowing.

Quercus robur (Pedunculate oak), Quercus petraea (Sessile oak)

Extraction and cleaning of acorns can easily be carried out before storage or sowing by floatation method. Sound acorns will sink to the bottom while defective, hollow and foreign debris, twigs and cups will float and can be removed. In general these oak species should not be stored as they lose viability if the moisture content of the seeds drop below c. 40%. Acorns of these species (unlike some other oak species) experience little or no dormancy and will germinate immediately after falling.

Sorbus aucuparia (Mountain ash)

Extract the seeds from the fruit and sow immediately after collection or dry the seed and store before pre-treating for spring sowing. Avoid high seedbed temperatures after sowing as this can induce secondary dormancy also. Mix seeds with moist stratification medium and give two weeks warm (21 – 24oC) and 12 – 16 weeks cold stratification (1 – 4oC).

The Teagasc Forestry Department issues an article on a Forestry topic every Friday here on Teagasc Daily

Subscribe to: Forestry e-News

Keep up-to-date with the Teagasc Forestry Department here or follow them on Social Media here